Updated Aug 9 2021

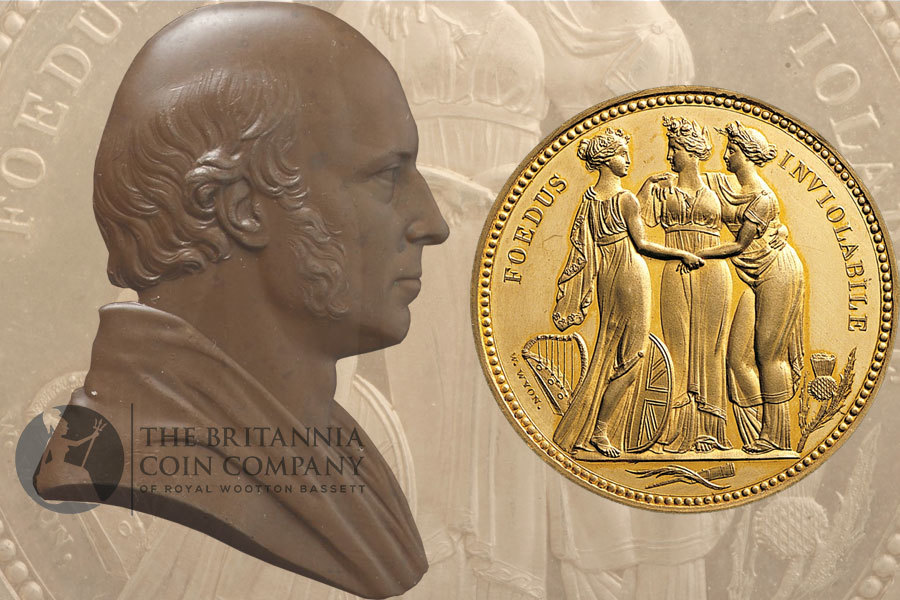

Created by the renowned engraver, William Wyon, early in his decorated career with the Royal Mint, the Three Graces is both exquisite and highly collectible.

This pattern coin never entered circulation but has earned a reputation for its attractive and symbolic reverse. Crafted at a momentous juncture in the history of British coinage, the story behind the design is a fascinating one. Today on The Britannia Coin Company blog we're investigating what makes this nineteenth-century design so sought after.

Silver Three Graces pattern crown from the collection of The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

National Personifications and Greek Myths

The obverse of this remarkable piece features a high-relief effigy of George III that is quite different from that which appears on contemporary circulating coinage. It preserves the King's distinctive features but is undeniably more flattering. The inscription reads 'GEORGIUS III D: G: BRITANNIARUM REX F: D: 1817'. The engravers name appears below the truncation of the neck as 'W. Wyon'.

But it's the reverse for which this coin is remembered. Encircled by the motto 'FOEDUS INVIOLABILE' (Inviolable or Unbreakable League) stand three female figures, dressed in a classical style. The implements at their feet – a harp, a shield bearing the cross of Saint George and an oversized thistle – give clues as to their identities as representations of Ireland, England and Scotland. Close examination detects further symbols in their crowns: shamrocks, roses and more thistles.

England - or maybe we should call her Britannia - is perhaps the elder sister, standing taller than the other women who look at her with affection. This is an idealised representation of the union between the three nations, formed as the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland in 1801. Wales is not represented here, but then that would have disrupted the neat parallel with the three charities of Greek mythology. The pattern coin certainly owes something to Antonio Canova's statue on that subject, though in the numismatic version the ladies are better dressed.

The Victoria and Albert Museum and the Scottish National Gallery jointly hold one version of Antonio Canova's sculpture, The Three Graces, which depicts three daughters of Zeus: Euphrosyne, Aglaea and Thalia. Edited, CC BY-SA 3.0.

Victory, Stability and the Great Recoinage

Below the figures of the Three Graces are two additional objects which scrutiny shows to be a rudder and a palm frond. In 1817 when the coin was first minted the connotation here would be clear: the palm indicates both victory and peace and the rudder reminds us of British naval supremacy.

The Three Graces was struck in the aftermath of the Battle of Waterloo and the effective end of the Napoleonic Wars. While the national mood was initially jubilant, decades of military and economic conflict had created fiscal troubles that could not be ignored. Expensive coalitions had left the national debt at more than double GDP. Trade disruptions had limited the supply of silver and copper from colonial outposts. On top of this, a bad harvest and artificially inflated corn prices were beginning to cause unrest.

The British government desperately needed to stabilise the currency. The first step in this process? The Coinage Act of 1816. Also known as Liverpool's Act, the law reintroduced silver coins and replaced the Guinea (valued at 21 shillings) with a new gold Sovereign (slightly lighter and valued at 20 shillings). This major turning point in monetary policy meant upheaval at the Royal Mint, then controlled by Master of the Mint, William Wellesley-Pole. New coins would be needed fast and for their designs Wellesley-Pole turned to the circle of artists and engravers that included William Wyon.

An Up-And-Coming Artist

When William Wyon crafted the Three Graces in 1817 he was in the middle of a meteoric rise. Born in Birmingham in 1795, Wyon came from a family of medallists and engravers. When he turned 14 he became apprenticed to his father, Peter Wyon: a die engraver for Soho Mint. William's uncle, Thomas Wyon Senior, as well as his cousin, Thomas Junior, were both employed by the Royal Mint.

In his late teens, William twice won the Royal Academy's silver medal for sculpture. In 1813, when he was 18, his entry to a Society of Arts, Manufactures and Commerce competition won a gold medal and earned him considerable attention in London's art scene. His high relief depiction of Ceres, a Roman goddess of farming, was adopted by the Society for its agriculture medal.

By 1816, William was settled in the capital and confident enough in his abilities to compete for the newly created post of Second Engraver to the Royal Mint. He was appointed to the position and began work under his cousin Thomas Junior, who was then Chief Engraver. Though he already had a thriving career, William also enrolled at the Royal Academy Schools, determined to perfect his craft.

John Flaxman's Influence

The art world that Wyon was establishing himself in was dominated by neoclassicism. Its proponents were influenced by stories of Ancient Greece and Rome and the simple, symmetrical style they saw in artefacts, engravings and on their Grand Tours. We see evidence of this movement in the paintings of Ingres, the empire-line gowns in Jane Austen adaptions and the columned facades of great buildings of the period, like the British Museum.

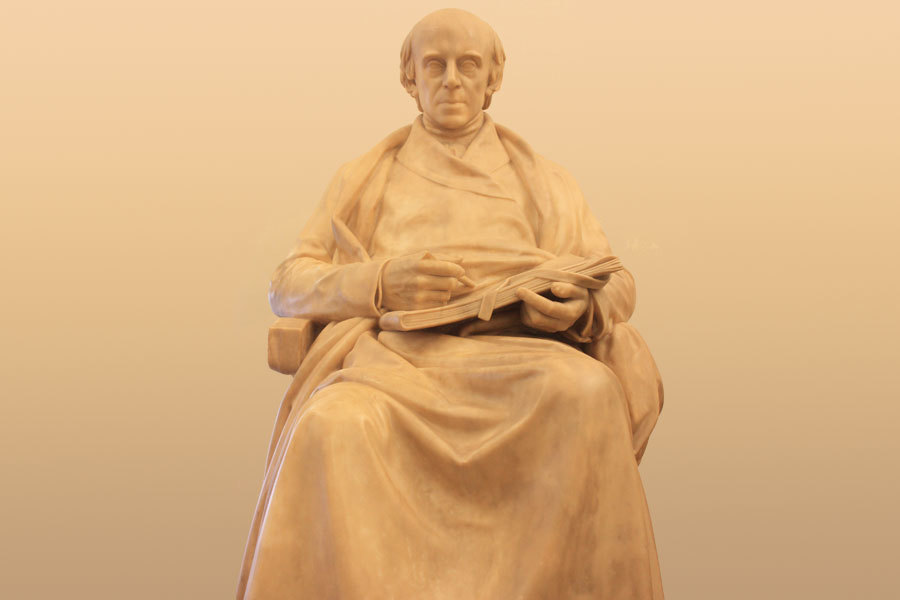

William Wyon was a pupil of one of the leading proponents of neoclassicism in Britain: John Flaxman. Flaxman was a sculptor and illustrator. His relief sculptures and works on paper had in common a clean-lined style, classical affectations and an inspiring sincerity that influenced many contemporary artists. He became a member of the Royal Academy in 1800 and was later appointed the first professor of sculpture at the Royal Academy Schools.

As one of Flaxman's students, Wyon would have learnt from his teacher that sculpture should be a:

'… representation of superior natures, divine doctrines and history … assisting in the elevation of our minds towards that excellence for which they were originally intended'

Wyon would apply this principle to his medallic work, seeing coin engraving not just as a technical exercise but as a vehicle for the most noble of Enlightenment principles. His Three Graces pattern, with its classical figures and thoughtful symbolism owes much to Flaxman's style and philosophy.

Sculpture of John Flaxman, William Wyon's mentor, by Musgrave Watson, University College London. Photograph by Stephencdickson, edited. CC BY-SA 4.0.

National Pride and Rivalry

As well as being a champion of neoclassicism, Wyon's teacher was also a patriot: proud of British art and artists. If Flaxman knew anything about it - and he likely did - he may have expected his pupil and countryman to become Chief Engraver at the Royal Mint, following the death of Wyon's cousin Thomas in 1817.

This was not to be the case, thanks to the explosive arrival in England of a Roman engraver, Benedetto Pistrucci. His masterful cameo engravings took the haut ton by storm and he was soon under the employ of Wellesley-Pole. It was he, rather than Wyon, who was commissioned to create a fresh portrait of George III to adorn the new sovereign.

While Pistrucci did not model the King from life and relied on others to craft dies, his bulbous portrait - nicknamed the Bull Head - was rightfully unpopular. According to his effusive biographer, Nicholas Carlisle, Pistrucci's ugly effigy was the impetus for Wyon to create an alternative pattern.

Carlisle, a friend of Wyon, records that he spend his limited free time first modelling his own likeness of the monarch and, for the reverse, designed the elegant expression of national pride that we know as the Three Graces. The initial snub and Wyon's artistic dig at the Italian-born Pistrucci marked the beginning of a decades long rivalry, played out by their supporters in the London newspapers.

A medallic portrait of William Wyon by his son, Leonard Charles Wyon. The elder Wyon's career with the Royal Mint lasted longer than Pistrucci's and his reputation has since become that of one of the finest engravers to work on British coinage.

Rare and Highly Sought After

Nineteenth-century strikings of the Three Graces were pattern coins. They were minted in limited numbers to assess the proposed design and then might have been sold or gifted. Proof patterns are important to collectors because they can be a record of numismatic history. Multiple variations may be present in pattern coins, including off-metal examples and piedforts. When there is no intention of mass production, engravings do not need to be in low-relief, providing more opportunity for detail and artistry. Pattern coins are typically scarce, increasing their value.

Only around 50 coins with the Three Graces pattern were ever struck, and only a few of those survive. One of three known gold specimens is in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. A silver example remained in the possession of the Wyon family, only coming to the market in 1962. In a September 2014 sale by St James's Auctions, this piece achieved a price of £48,000, well above estimates and more than double the price achieved at its last sale in 2005.

In January 2020 another extant example, graded Proof 65 by NGC, sold for $156,000 (approximately £120,000). It's clear that Wyon's Three Graces pattern crown is only increasing in reputation as a masterpiece of numismatic art, the work of a truly great engraver.

The Great Engravers’ Legacy

Owning a real 1817 Three Graces is beyond the reach most collectors. It’s good news then, that the pattern has recently been reissued in a range of different sizes and metals, meeting overwhelming demand.

In 2020 the Three Graces became the second of Wyon’s designs to be offered as part of The Royal Mint’s successful The Great Engravers Collection. The designer’s Una and the Lion - crafted later in his career - was remastered for a new generation and released to acclaim in 2019. The Royal Mint’s 2020 Three Graces was offered in silver and gold proof and here at The Britannia Coin Company we were pleased to retail some of the scarcest strikings, including:

2020 The Three Graces by William Wyon - 1Kg Gold Proof : Royal Mint Great Engravers Series

2020 The Three Graces by William Wyon - 1Kg Silver Proof : Royal Mint Great Engravers Series

The Royal Mint’s website sold out of Three Graces coins lightning quick so its lucky that we've secured exclusive rights to gold and silver proof Three Graces from the Commonwealth Mint, issued for the British territory of Alderney. We’ve still got a limited stock of 2020 Alderney Three Graces coins, including:

2020 Alderney 'The Three Graces' Gold Proof Five Pounds : PCGS PR70 Graded

2020 Alderney 'The Three Graces' 3 Coin Sovereign Set : PCGS PR70 'First Strike'

2020 Alderney 'The Three Graces' 5oz Silver Proof Twenty Five Pounds : PCGS PR70 Graded

Additionally, in 2021 the Three Graces appeared as the first release in a new series from The East India Company called The Masterpiece Collection. Minted in cooperation with the island of Saint Helena, these 2021 Three Graces coins are also available in both gold and silver proof. We’ve got a few remaining pieces, including:

2021 Saint Helena Three Graces 2 Ounce Gold Proof

2021 Saint Helena Three Graces 5 Ounce Silver Proof

Frequently Asked Questions

The Three Graces is the name given to a pattern crown, designed by William Wyon early in his career. This scarce coin is known for its reverse which features three female figures, representing England, Scotland and Ireland. The design was never in circulation but demonstrates Wyon's renowned talent. It also unlocks a story of rivalry, a revolution in British currency and a relationship between Wyon and his teacher, John Flaxman that would bring neoclassical style to nineteenth-century coinage. Surviving examples achieve significant prices at auction.

William Wyon's Three Graces pattern crown features three female figures, designed to represent England, Scotland and Ireland. The shield, thistle and harp at their feet confirm this interpretation. The graces' affectionate embrace suggest a harmonious union between the nations that in 1817 made up the United Kingdom. A rudder and a palm frond also nod to British naval supremacy and its role in the peace that followed the Battle of Waterloo. A double meaning may be found in comparing the coin to the three graces of Greek mythology, featured in many notable artworks.

The Three Graces pattern crown is valued by collectors for its craftsmanship and its rarity. A pattern coin, it was only struck around 50 times making the surviving examples both scarce and valuable. The engraver, William Wyon, was well known in his day and is widely regarded as one of the greatest engravers to ever work on British coinage. While some of his designs for coinage are commonplace, the Three Graces is hard to come by with examples achieving prices of £120,000 in 2020. Specimens of this attractive, symbolic design make a show-stopping addition to any serious collection.

William Wyon was a prolific nineteenth-century engraver, well-loved for his finely-wrought, neoclassical designs. He was employed by the Royal Mint from 1816 as Second Engraver before becoming Chief Engraver in 1828. During his long career he executed dies for many notable coins, including the 'Young Head' effigy of Queen Victoria, the Una and the Lion five pound piece and the beautiful but ultimately unused Three Graces pattern. His son, Leonard Charles Wyon was also a notable medallist and Chief Engraver.

Decades of conflict had pushed the national debt to more than double GDP and curtailed the flow of copper and silver from across the Empire. With corn prices high in the aftermath of the Treaty of Paris and the domestic market contracting, there was an extreme need to stabilise the currency. This was achieved through what is called the Great Recoinage of 1816. A new sovereign replaced the guinea and silver coinage was reintroduced. These new coins called for new designs which were executed by great engravers like William Wyon and Benedetto Pistrucci.

The design of the Three Graces owes much to the neoclassical style that dominated the decorative and visual arts of Europe in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth-centuries. Works associated with this movement are identified by a deceptively simplistic, clean-lined style and a reverence of the art of ancient world. The Three Graces shows the influence of neoclassicism in the classical dress worn by the three figures and the allusion to the three charities of Greek mythology. William Wyon, the engraver, was influenced by his mentor, John Flaxman, a leading proponent of neoclassicism.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)