.jpg)

Updated Aug 10 2021

Benedetto Pistrucci's Saint George and the Dragon design is synonymous with the Sovereign and instantly recognisable to coin collectors. Crafted more than 200 years ago, this iconic engraving has appeared on currency issued by nearly every British monarch since George III.

But how did this beautiful image come to feature on the Sovereign? Why was the tale of St George and the Dragon chosen in the first place? And what is it about this motif and the Sovereign itself that has such enduring appeal?

With Pistrucci's most famous work again featuring on the 2021 Sovereign, we're delving into the legend of Saint George, the life of a tempestuous Italian artist and the fascinating story behind the rebirth of the modern Sovereign.

George and the Dragon on the 2021 Gold Proof Sovereign, minted to celebrate the Queen's 95th birthday.

A Passionate Artist

We think of Saint George and the Dragon as a very British subject, but the creative genius behind the design was born in Rome in 1783. Benedetto Pistrucci was already famous when he arrived in London in 1816, though it was in his new home that he would create his best remembered work.

Pistrucci didn't train as a coin engraver: his first love was carving gemstones. The cameos and intaglios he produced, featuring characters from Greek and Roman mythology, were so good that more than one buyer was fooled into thinking they had acquired a real antique.

While Pistrucci's talents earned him commissions from Dukes, Counts and Princesses, he wasn't always popular with other artists. In his youth, a fight with fellow apprentices had got him stabbed. Later in life, he was known to reject prestigious commissions if he was denied full creative control.

Sardonyx cameo of Pistrucci by his daughter, Maria Elisa Pistrucci, c1850. Collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

The Great Recoinage

Pistrucci arrived in England in the immediate aftermath of the Battle of Waterloo. This was a time of great public celebration but it was impossible to ignore the economic difficulties that wartime silver shortages and gold hoarding had wrought. British currency desperately needed stabilising.

Parliament sought to fix the problem with an enormous recoinage programme, leaving the Master of the Royal Mint, William Wellesley-Pole, searching for fresh designs. Pistrucci, who had just entered the capital's art scene with a splash, came to Wellesley-Pole's attention at exactly the right time.

As soon as he was on the Mint's payroll, Pistrucci was put to work designing a new portrait of King George III for urgently needed silver coins. It was not a successful first outing. Pistrucci's effigy, first issued on the 1816 Half Crown, was unflattering, unpopular and quickly redesigned.

Pistrucci's bulging, bug-eyed Bull Head on an 1817 George III Silver Half Crown.

Resurrecting the Sovereign

Despite bad reviews of his first coin project, Wellesley-Pole kept Pistrucci's on for the next phase of the Great Recoinage: the introduction of a new gold coin. Designed to replace the one-pound banknotes issued during the Napoleonic Wars, the coin was to be called the Sovereign.

The name was probably chosen to evoke the prestige of an earlier English gold coin, issued first during the reign of Tudor King Henry VII. These older Sovereigns were much larger and heavier than the new coin which was to weigh 7.988 grams, with a consistent 7.322 grams of that being gold.

Wellesley-Pole sought 'perfect form and exquisite taste' in choosing a design to grace the first new Sovereigns. The obverse would, of course, bear the face of the ageing King, but he wanted something distinctive for the reverse, not the heraldic devices that had been common for centuries.

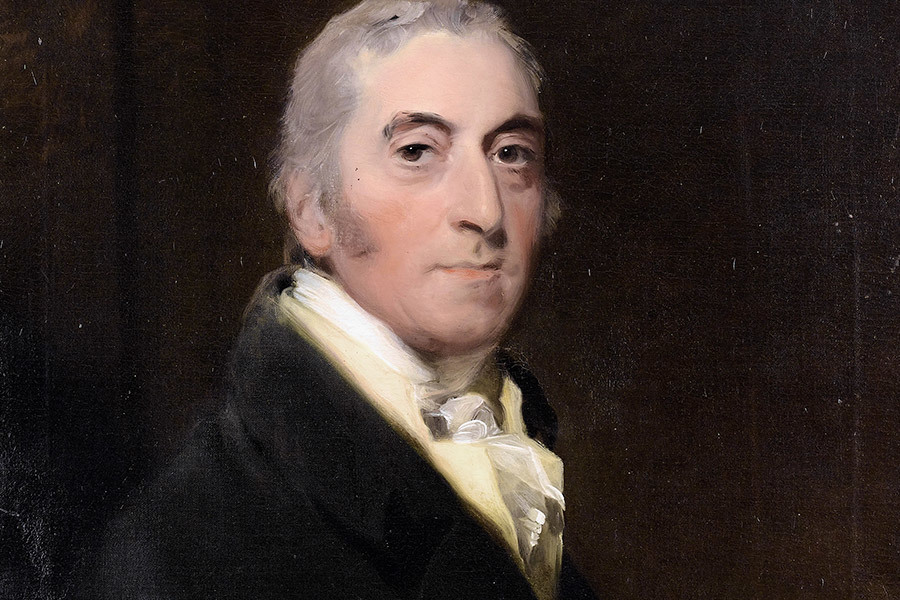

William Wellesley-Pole oversaw the reintroduction of the Sovereign in 1817. Portrait by Thomas Lawrence.

Lady Spencer's Commission

The reverse that Wellesley-Pole chose was inspired by a cameo, commissioned from Pistrucci by Lavinia Spencer, Countess Spencer, for her husband to wear as part of his Knight of the Garter regalia. The Order of the Garter is dedicated to Saint George so the choice of subject was obvious.

The cameo Pistrucci carved for Spencer was not unique in conception. It owed much to a shell cameo in the collection of the Duke of Orleans. It may also have been inspired by the mounted riders that appear in the Parthenon Sculptures or Elgin Marbles, sold to the British government in 1816.

Regardless of the originality of the composition, Pistrucci produced a charming engraving for the Countess. As his model he used an Italian waiter, employed at a Leicester Square hotel. Wellesley-Pole, on seeing the completed cameo, decided the motif was suitable for the new coinage.

Pistrucci loved to study ancient artefacts. Could he have been inspired by the Elgin Marbles? Photo by Paul Hudson. CC BY 2.0.

England's Patron Saint

Why George and the Dragon? Saint George had been venerated as England's principal saint since the Middle Ages, despite the historical George being from Turkey. In the early 1800s, with the country ruled by a succession of Georges – also not of Anglo-Saxon stock – the Saint's cult was ascendant.

Undoubtedly the most famous tale associated with Saint George involves him slaying a dragon and thus freeing the city it had been terrorising. Stripped of its detail, the story is a battle of good and evil, easily compared to other conflicts, the pertinent example in 1817 being the war with France.

Dispatching a dragon got George venerated as a warrior saint and Waterloo got the Duke of Wellington the same level of name recognition. It's easy to suggest that the diminutive trampled beast is Napoleon while the hunk on the horse is the Field Marshall responsible for the Pax Britannia.

An armoured Saint George coolly dispatches a crocodile-like dragon while an angel watches on in this 1866 painting by Edward Burne-Jones from the Art Gallery of New South Wales.

Mastering Steel Engraving

To turn the piece he had carved for Lady Spencer into a coin would take skills Pistrucci did not have at the beginning of 1817. His earlier effigy of George III had been converted from a jasper cameo by the Royal Mint's engravers and Pistrucci blamed them for its poor reception.

A driven perfectionist, Pistrucci took up the art of steel engraving himself to complete the Sovereign commission. Thanks to his background in gem-engraving, Pistrucci was used to working on the small scale required for coinage, but metalwork required a very different set of tools and talents.

The matrix that Pistrucci cut for the Sovereign in mid-1817, featuring his George and the Dragon pattern, shows that he picked up the knack quickly. The design was quickly adopted and has since been recognised as among the most beautiful to ever grace British coinage. Pretty good for a first go.

'The reader must be aware that this work was the first I did with the graving-tool, without ever having seen anybody engraving in steel; it is therefore not one of my best, but one should bear in mind that it requires ten years practice to do such work well.'

– Extract from a note by Pistrucci, discussing engraving the Sovereign.

Sketch by Pistrucci for his iconic George and the Dragon Sovereign from The Royal Mint collection. A wax model for the piece also survives in the collection of the British Museum.

The 1817 Sovereign

Pistrucci's George and the Dragon, as it appeared on 1817 Sovereigns, is very different to other coins of the period. The customary coat of arms is replaced with a scantily garbed soldier, mounted on a horse that rears over a dying dragon, slain with a spear that has broken in the struggle.

The central device is encircled by a stylised garter which bears the inscription 'HONI · SOIT · QUI · MAL · Y · PENSE': the motto of the aforementioned Order of the Garter, an order of chivalry founded by Edward III in 1348. Translated, the Latin phrase means 'shame on anyone who thinks evil of it'.

Pistrucci's and Wellesley-Pole's initials both feature on the 1817 Sovereign: the artist's 'B P' can be found beneath the broken shaft of the spear while 'W W P' appear on the garter buckle. Pistrucci also prominently signed his portrait of George III which featured on the obverse.

1817 George III Gold Sovereign, the first circulating coin to feature Pistrucci's much-admired George and the Dragon design.

Mixed Reviews

Those initials were one thing that the Regency art world took issue with. Wellesley-Pole was perfectly entitled to identify himself on coins issued during his time as Master of the Mint but he was lambasted for it. Responding to this critique he referred to an earlier numismatic controversy:

'I shall be impeached for putting my initials on the coin of the realm, as Cardinal Wolsey was for placing a cardinal's hat on the coin of Henry VIII!'

As well as questioning the 'vanity and presumption' of Pistrucci's signing his work, letters published in the newspapers also expressed dissatisfaction than an Italian artist should be responsible for British coins. Their anonymous authors preferred another gifted engraver, William Wyon.

To the annoyance of many, Pistrucci remained in the employ of the Royal Mint until his death in 1855. Though his status as a foreigner prevented Wellesley-Pole from appointing him Chief Engraver, his designs - most famously George and the Dragon - secured his legacy.

Spears, Swords and Silver

The 1821 Sovereign, the first issued under George IV, saw Saint George wielding a sword, rather than a lance. The streamer on his helmet is gone and so is the garter that encircled the central motif on earlier Sovereigns. Instead, the reverse of this coin bears the year of issue, missing previously.

The pattern also saw use on the extremely rare 1820 Five Pound Piece and Double Sovereign, struck only as proofs shortly after the death of George III. Though the George and the Dragon design is powerfully associated with the Sovereign, it was also used on Crowns issued from 1818 to 1820.

On these silver coins, the spear-for-sword switch is present from the first issue and 'PISTRUCCI' runs below the image: a middle finger to the critics? The legendary motif again appeared on Crowns issued late in the reign of Queen Victoria and on the Crowns of her eldest son, Edward VII.

George and the Dragon on an 1888 Queen Victoria Silver Crown with a wide date variation.

Standing the Test of Time

After George IV's death, Pistrucci's George and the Dragon engraving fell out of use on Sovereigns for decades. It is absent from William IV's coinage. The design was finally revived for use on gold coins in 1871, surviving the redesign that coincided with Queen Victoria's Golden Jubilee in 1887.

The design has continued as a mainstay of British coinage ever since. Edward VII and George V's Sovereigns use it and it was intended to grace the Edward VIII's coinage as immensely rare proof coins show. George and the Dragon again appears on highly collectible George VI Sovereigns.

By the time Elizabeth II came to the throne in 1952, Sovereigns were not being struck for circulation in Britain. In 1957 the coin was re-introduced. Proof, Brilliant Uncirculated and Bullion versions are now issued annually, with Pistrucci's much-loved design reused, remastered and reinterpreted for new generations.

A reinterpretation of Pistrucci's George and the Dragon motif by British sculptor Paul Day on the 2012 Sovereign.

Frequently Asked Questions

The iconic George and the Dragon design that features on the British Sovereign was designed by Italian artist Benedetto Pistrucci. A cameo maker by trade, Pistrucci learned the art of steel engraving to complete the commission for the first modern Sovereign, struck in 1817.

Benedetto Pistrucci's George and the Dragon design has been used on Sovereigns since the modern version of the coin was first struck in 1817. Saint George is the patron saint of England, closely associated with the monarchy, and the story of his victory over the dragon is his best-known legend.

The George and the Dragon design, engraved by Benedetto Pistrucci, first appeared on British Sovereigns in 1817. Since then, the design has been used on the coins of every British monarch with the exception of William IV. Over the years, Pistrucci's motif has been adapted and reinterpreted.

The well-love George and the Dragon pattern, designed by Benedetto Pristrucci has appeared on Sovereigns issued by every British monarch since George III with the exception of William IV. It has also been used on Crowns, Two Pound Pieces (Double Sovereigns) and Five Pound Pieces.

The George and the Dragon motif that appears on the reverse of many British Sovereigns is a beautiful and memorable design. Used for over 200 years, its long history makes it instantly recognisable to anyone interested in coins or England's patron saint.

Browse the Britannia Coin Company's wide range of Sovereigns to find the coin that's right for you. We sell historic Sovereigns featuring Benedetto Pistrucci's George and the Dragon design as well as more modern commemorative issues that feature remastered versions of this iconic design.

The story goes that St. George slayed the dragon on Dragon Hill, Uffington, which is just 20 miles from where The Britannia Coin Company is located.

.jpg)