Updated on Dec 4 2023

If you're interested in the history of British coin designs, you'll recognise the name Benedetto Pistrucci as the artist behind the iconic George and the Dragon motif, still used on the Sovereign today. But what else do you know about this celebrated Italian engraver?

A star in his own lifetime, Pistrucci engraved portraits of Kings and Emperors during a high-flying, international career, buffeted by the drama of the Napoleonic Wars. An ambitious but polarising character, Pistrucci stoked rivalries, survived a stabbing and left an indelible mark on British coinage.

With the limited edition 2024 Sovereigns again featuring Pistrucci's most famous design, we're exploring his life and legacy in today's blog. Read on for a detailed biography of the celebrated Royal Mint engraver.

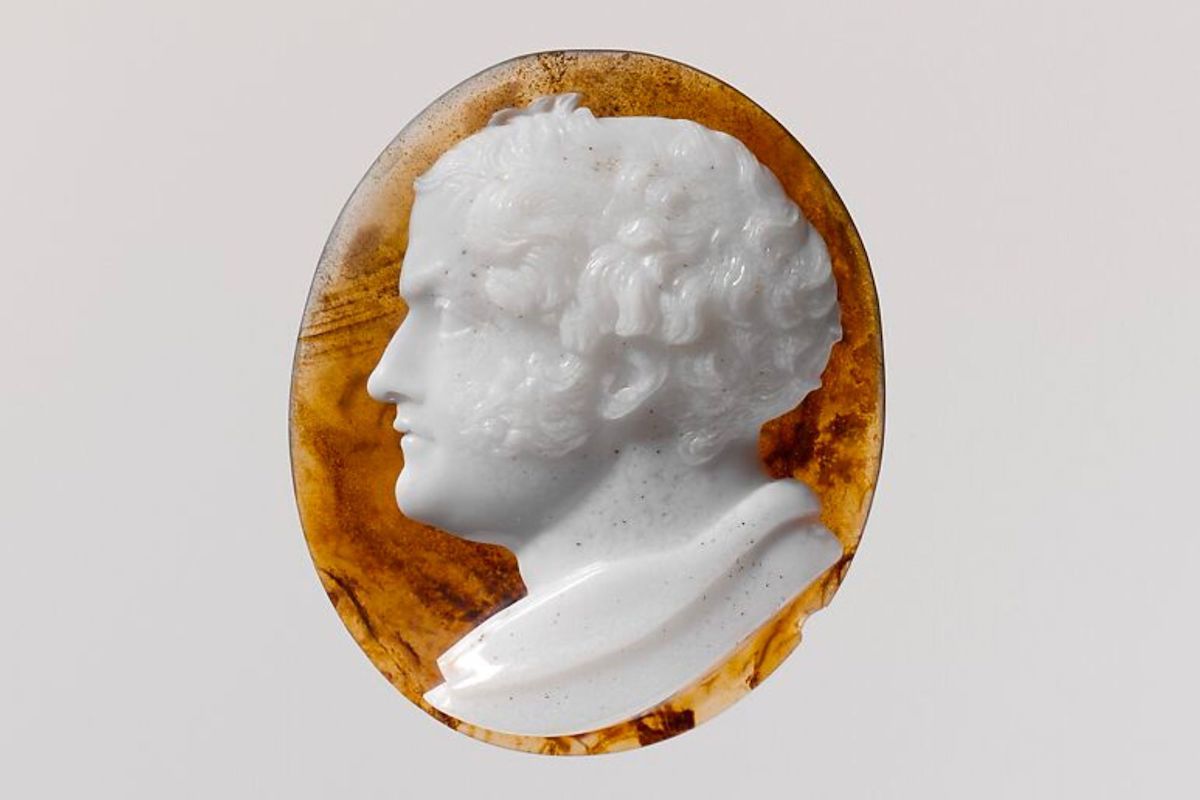

Sardonyx cameo of Pistrucci by his daughter, Maria Elisa Pistrucci, c1850. Collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

A Turbulent Childhood In Italy

Benedetto Pistrucci was born in Rome on 24 May 1783: not 1784 as is often stated. His father was a senior judge who had prosecuted supporters of the French Revolution, resulting in a bounty of 1,000 Louis D'or being placed on his head as the War of the First Coalition escalated.

With the French Army of Italy advancing, the Pistrucci family vacated properties in Bologna, then moved from Rome to Naples. Through these years the young Benedetto endured an undistinguished education in Latin while demonstrating a talent for carving small toys out of wood.

As a teen Pistrucci worked for a painter, then a gem-engraver in Rome where his family returned following the Peace of Leoben. The move meant Pistrucci could study the works of Raphael and Michelangelo, as well as the Greek and Roman antiquities that were exhibited and sold in the city.

What is Gem Engraving? Gem engraving is the art of carving semi-precious gemstones, either by cutting into the surface of the gem – creating an intaglio – or working in relief, leaving a raised image called a cameo. Gem engraving has been practiced since ancient times and requires great skill as the work is small and the medium expensive.

Fighting For Fame

Pistrucci's tutor favoured his work, annoying his fellow apprentices. Tensions escalated into a violent fight in which Pistrucci was stabbed. While recuperating he taught himself to make beeswax models, leveraging this skill to acquire a new job with the eminent gem engraver, Nicola Morelli.

Though only about 15 at the time, Pistrucci was already busy with his own commissions which reportedly earned him Morelli's ire too. They soon parted ways which does not seem to have harmed Pistrucci's growing reputation with cameo dealers and wealthy Italian art collectors.

Pistrucci's most significant early patron was Elisa Bonaparte, who Pistrucci worked for in Florence for several years. He modelled Elisa's brother, Napoleon, during a trip to Paris in 1815. His portrait of the Emperor, rendered in wax during the Hundred Days, was probably the last completed in Europe.

The Emperor Napoleon by Jacques-Louis David, 1812. Collection of the National Gallery of Art. Pistrucci's own portrait of Napoleon is now in the collection of the Victoria and Albert Museum.

Gem Engraving And Ancient Forgeries

Nineteenth-century gem engravers employed techniques that had changed little for millennia. This made the creations of Pistrucci and his contemporaries almost impossible to distinguish from ancient cameos. While Pistrucci claimed he never sold his engravings as antiques, his unscrupulous dealers certainly did.

This led to a fateful run-in, shortly after Pistrucci relocated to London, with Richard Payne Knight, a scholar and collector. Knight showed him a cameo fragment, acquired at great expense as a relic and depicting the Roman goddess Flora, which Pistrucci immediately recognised as his own work.

Though embarrassing for Knight, the incident only enhanced Pistrucci's reputation in England. He capitalised on it by cutting multiple versions of the Flora cameo, including one for Sir Joseph Banks – renowned naturalist and President of the Royal Society – who would promote Pistrucci's career.

The Great Recoinage Of 1816

It was through Banks that Pistrucci would come to the attention of Master of the Royal Mint, William Wellesley-Pole. Banks commissioned Pistrucci to carve a red jasper cameo of George III, after a coin portrait by Nathaniel Marchant. This was shown to Wellesley-Pole who was duly impressed.

In 1816 the Master of the Mint was busy overseeing what became known as the Great Recoinage: an effort to restabilise British currency in the aftermath of the Napoleonic Wars. Based on the cameo, Pistrucci was commissioned to make models of the King that could be used on gold and silver coins.

"I have thought it desirable to employ Mr Pistrucci, an artist of the greatest celebrity, whose work places him above all competition as a gem engraver, to make models for the dies for the new coinage …" – Wellesley-Pole in a letter to the Treasury, June 1816.

Pistrucci's designs, modified and cast by Royal Mint engravers, quickly appeared on the obverse of the Half-Crown, Shilling and Sixpence. Dubbed the 'Bull Head', the effigy was not popular, inciting the perfectionist Pistrucci to blame the Royal Mint's craftsmen and take up steel engraving himself.

Pistrucci's unflattering Bull Head effigy of King George III on an 1817 silver Halfcrown. The portrait was changed for later issues.

St George And The Dragon Sovereign Reverse

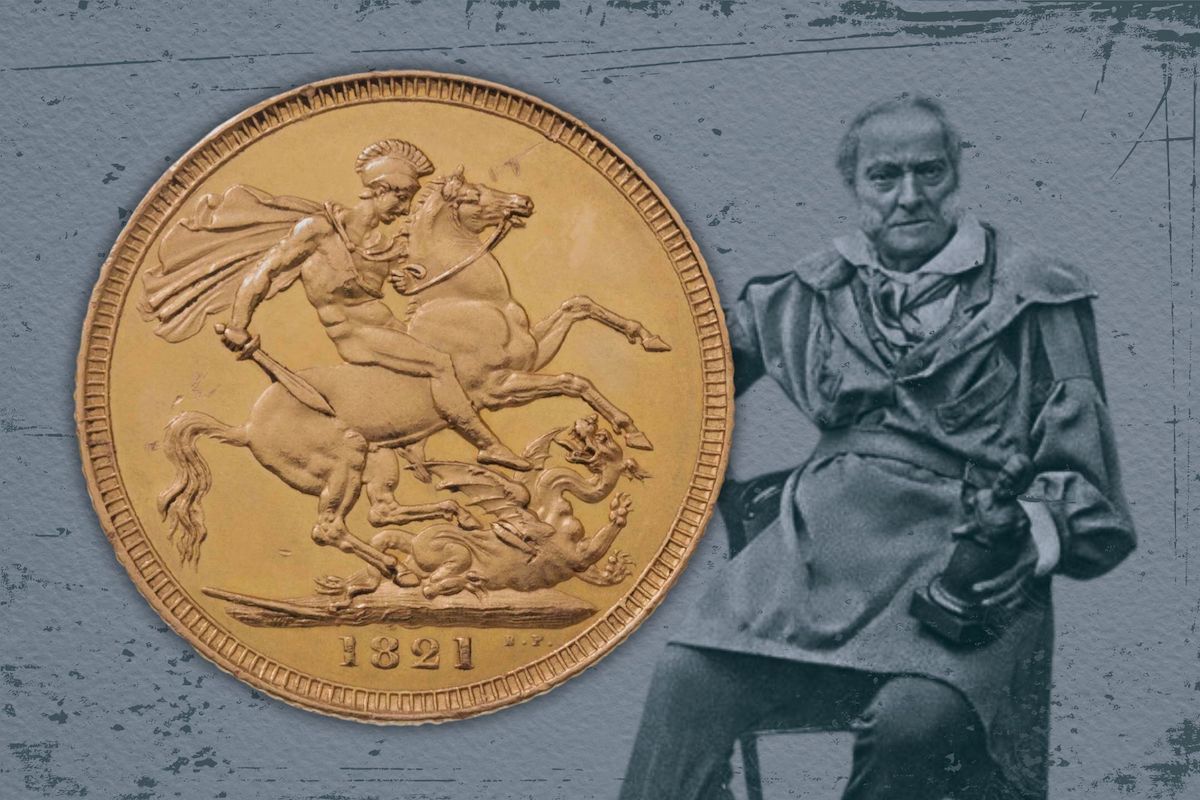

Wellesley-Pole sought 'perfect form and exquisite taste' in the coins he commissioned and he certainly found this in the next design he sought from Pistrucci. Inspired by a cameo carved for Lady Spencer, Wellesley-Pole contracted Pistrucci to craft the reverse of the new Sovereign.

For a fee of 100 Guineas, Pistrucci created a coin regarded by some as the most beautiful ever produced. His timeless George and the Dragon motif featured on the first modern Sovereign, minted in 1817 under King George III, and was used on Sovereigns of King George IV, Queen Victoria and every subsequent British monarch.

Pistrucci's Saint George is nude but for a helmet, evoking an ancient Greek warrior, in a dynamic portrayal that sees the Saint triumphing over a beast, trampled beneath his horses' hooves. Pistrucci worked from life, using a hotel waiter to pose as England's patron saint for this iconic engraving.

Reverse of an 1817 full Sovereign featuring Benedetto Pistrucci's classic St George and the dragon motif.

Rivalry With William Wyon

The prestigious commissions Pistrucci was given by the Royal Mint left him well placed to take up the post of Chief Engraver when it fell vacant in September 1817. He took over the responsibilities and drew the salary but his status as a foreigner left him barred from the position.

Pistrucci was not pleased by this situation but neither were supporters of another Royal Mint engraver and contender for the Chief Engraver position, William Wyon. Then Second Engraver, Wyon was also immensely talented, producing designs like the Three Graces and Una and the Lion.

Over the next decade a rivalry played out between Pistrucci and Wyon via their respective proponents in the London newspapers. It is hard to say what the personal relationship was like between the pair who effectively job-shared until Wyon was appointed to the coveted role in 1828.

Innovations And Inventions

Despite negative comparisons of his workmanship to Wyon's, Pistrucci was undoubtedly passionate about his craft. As well as producing beautiful and memorable designs, he also contributed to developments in techniques and technology that changed minting in the nineteenth-century.

During a visit to Paris with Wellesley-Pole, Pistrucci purchased an early reducing machine or pantograph lathe. The first such machine to be used by the Royal Mint, it could reproduce and resize dies, offering cost and time savings over the laborious hand production methods used before.

Pistrucci also claimed to have developed a method of quickly making wax or clay models into dies, involving a plaster of Paris cast, a sand impression of which could then be cast in iron. Whether he invented this pioneering practice or not, Pistrucci was certainly employing it from the 1830s.

'It requires very little discrimination to perceive that by this invention a gigantic stride has been made … we shall be able to multiply medals bearing original designs at a comparatively trifling expense' – Extract from a letter titled 'Pistrucci's Invention', printed in the Numismatic Chronicle of 1838-39.

Pistrucci's Later Role In British Coinage

In 1823, Pistrucci's champion, Wellesley-Pole, resigned from the Royal Mint after a momentous 11 years at the helm. The new Master of the Mint, Thomas Wallace, and his successor George Tierney, were not so accommodating of Pistrucci's disruptive attitude and need to model portraits from life.

Wellesley-Pole had managed to get Pistrucci sittings with the then Prince Regent for the portrait that would feature on his first coins as George IV. When a new effigy was requested by Wallace, Pistrucci refused to copy a bust by Sir Francis Chantray and the job was instead given to Jean Baptiste Merlen.

This workplace conflict did not get him stabbed but did mean Pistrucci had little to do with British coinage thereafter. The 1825 coins issued by George IV were completed by Merlen and Wyon while Pistrucci focused on medals and teaching as well as taking on gem commissions for private clients.

'I feel certain to surpass them all; therefore, the higher any of them stands, he only elevates me' – Pistrucci displaying his renown modesty in a letter.

What are you looking at? Pistrucci as an old man by an unknown photographer.

Pistrucci's Official Waterloo Medal

In 1828 – when Wyon was appointed Chief Engraver – Pistrucci was given the title of Chief Medallist, recognising a decade of high-quality medallic work. He had crafted a proposed medal to celebrating the purchase of the Elgin Marbles in 1816, as well as coronation medals for George IV and Victoria.

Pistrucci's most significant medal commission, however, was the Waterloo Medal. Proposed in the immediate aftermath of the victory, Pistrucci was paid a large sum upfront and then procrastinated the piece for more than 30 years, finally submitting the completed matrices in 1849.

By this point, the four Allied leaders whose profile busts featured on the obverse were dead and so were many of the intended recipients. Only electrotype examples were struck of the large and lavishly detailed medal. It was to be Pistrucci's final completed work before his own death in 1855.

Obverse detail from a bronze electrotype of Pistrucci's Waterloo Medal. Collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Frequently Asked Questions

Benedetto Pistrucci was an Italian engraver, first of gemstones and later of coins and medals. His most famous work is undoubtedly the George and the Dragon motif that has featured on the Sovereigns of every British monarch since George III. He is remembered for his skill and fiery temper.

Pistrucci was recruited to design coins for the Royal Mint by Master of the Mint, William Wellesley-Pole in 1816. He sought the role of Chief Engraver but foreigners were barred from the job. He attained the post of Chief Medallist in 1828 and remained in the employ of the Mint until his death.

Pistrucci's most famous coin design is undoubtedly for the Sovereign. He designed an iconic George and the Dragon pattern that featured on the reverse of the first modern Sovereign, issued in 1817. This celebrated engraving has been continually reused on Sovereigns for the last two centuries.

Pistrucci engraved several effigies of monarchs for coins and medals, including the controversial Bull Head effigy of George III which first appeared on the 1816 Half-Crown. The bulbous portrait was not popular and was quickly revised for subsequent issues of George's post-1816 coinage.

Pistrucci and William Wyon were both candidates for the post of Chief Engraver when the prestigious Royal Mint position fell vacant in 1817. However, the post was left unfilled while their respective supporters sung the praises of one and decried the other in the London newspapers.

Pistrucci is most famous his iconic George and the Dragon design that has featured on Sovereigns issued by every monarch since George III. The Italian engraver is also known for his Bull Head effigy, the never-struck Waterloo Medal and his apparent rivalry with his colleague: William Wyon.