We've got lots of new hammered silver pieces live on The Britannia Coin Company website right now, from some lovely Elizabethan Shillings to some fascinating (and affordable) Crusader coins. Today on the blog though, I want to focus in on an unassuming pair of Tudor Groats.

Left: 1544-1547 Henry VIII Hammered Silver Groat MM WS Bristol, right: 1547-1549 Edward VI Hammered Silver Groat Posthumous Henry VIII Bristol Mint.

These silver coins were minted in Bristol in the late 1540s. The first was struck at the very end of king Henry VIII's reign. The second also bears Henry's portrait but was issued posthumously by his son, Edward VI.

I'll be honest: they're not lookers. But they've got a fascinating mint mark which unlocks the story of a historic scandal with ties to Wiltshire - our home county - and a controversial Tudor policy that risked damaging the reputation of English coinage forever.

The Bristol Mint

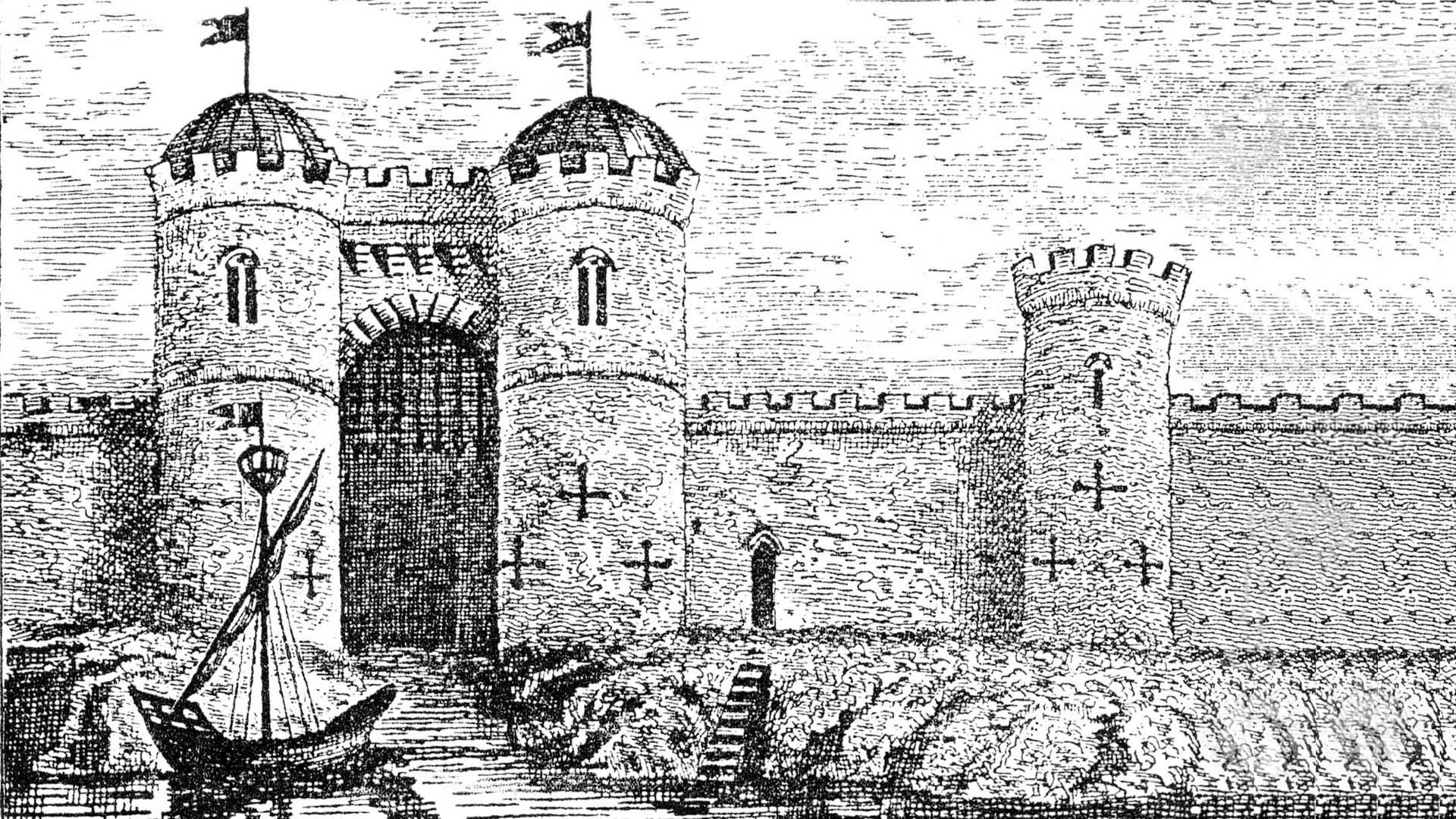

A mint operated intermittently in Bristol from at least the reign of Cnut the Great (1016-1035), perhaps earlier. The facility, based at Bristol Castle, was one of a number of regional mints that opened, closed and were revived through the medieval period.

The Norman castle that housed the Tudor mint of Bristol was levelled in the 1650s. From a nineteenth century publication on the city.

In 1542 Bristol became a city and a bishopric. This meant the when the Bristol Mint was reopened in 1546, its moneyers were empowered to strike coins with a reverse that read 'CIVITAS BRISTOLIE'. Earlier issues bore legends with a variation on 'VILLA BRISTOLIE'. The new mint was instructed to strike gold coins - the only facility outside London authorised to do so - as well as money for Ireland: previously the remit of the Tower Mint.

Records survive listing the staff hired to man the new branch mint. The king, Henry VIII, formally held the office of Treasurer while the Under-Treasurer and effective master is recorded as one William Sharington.

Who was William Sharington?

Born around 1495 into an undistinguished Norfolk family, William Sharington had made a rapid ascent into high court circles, mostly thanks to savvy marriages. He had served his time in various prestigious but slightly demeaning positions like page of the king's robes (royal wardrobe assistant) and by the mid-1540s he was a member of parliament and on his way to a knighthood.

.jpg)

Sharington was important enough to be the subject of a portrait drawing by royal painter Hans Holbein. Dated 1540-1543, now in the Royal Collection.

Sharington solidified his growing power by buying up property. He would come to own more than 14 manors and estates, primarily in Wiltshire, the most famous being Lacock Abbey, now owned by the National Trust.

Sharington's lands brought in revenue, as did his shipping endeavours and a moneylending side-line. But these activities weren't profitable enough to fund his lifestyle. His prestigious appointment at the Bristol Mint had the potential to plug holes in his budget, particularly if he was prepared to take some risks.

Groats minted in the early months of William Sharington's tenure at the Bristol Mint - before the death of Henry VIII in January 1547 - bear a distinctive three quarter bust and a 'WS' monogram mint mark, both seen on this 1544-1547 Henry VIII Hammered Silver Groat MM WS Bristol.

The Great Debasement

Henry VIII, like Sharington, lived beyond his means. His most successful money-making scheme - the dissolution of the monasteries - netted him enough for wars in Scotland and France but by the 1540s he was casting about for new sources of revenue.

A solution presented itself in reducing the amount of precious metal used to make coins. By increasing the amount of base metal used, Henry could get more coins for less bullion, saving himself a packet in the process. Gold and silver coins of a reduced fineness were minted surreptitiously from 1542 before being released into circulation in 1544. This practice escalated as Henry's reign drew to a close until the intrinsic value of some coins was as low as one sixth of earlier issues.

Why was debasement a problem? Coins with higher fineness are often hoarded while debased currency remains in circulation. This principle is known as Gresham's Law, named after English merchant and financier Sir Thomas Gresham.

We see the effects of this official debasement policy in extant coins, the generally poor grade of which betrays their composition. The problem was readily apparent to contemporary commentators, including the poet and playwright Thomas Heywood who published an epigram on the subject:

'These Testons looke redde: how lyke you he same;

Tys a token of grace: they blushe for shame.'

Heywood's conceit here rests on the notion that the significant copper content of Henry's silver coins, including the Testoon – the Tudor forerunner of the Shilling – made the portrait appear to blush in humiliation as they degraded.

The unusual forward-facing effigy that appeared on Henry VIII's Testoons bears similarities to this arresting portrait of the king after Hans Holbein's lost original. From the collection of the Walker Art Gallery.

Lining His Pockets

The Bristol mint was brought into operation to facilitate this embarrassing programme of state-sponsored debasement. Sharington's crime was that he compounded this notorious chapter in the history of English fiscal policy by perpetuating the debased coinage for his own profit rather than the state.

Soon after Henry's young son Edward became king, his regency council made some lethargic moves to clean up the monetary mess that his father had instigated. In April 1548, Testoons – synonymous with poor metal quality – were demonetised and recalled. This created a cracking modern collector's market for top-grade surviving examples but didn't do much to tackle the broader lack of confidence in the currency which still contained fractional amounts of gold and silver.

Sharington, overstretched by his property empire and largess, continued minting Testoons through 1548, after Edward's administration had condemned them. He could profit from the recall of these coins but in doing so he was risking imprisonment and his neck if his embezzlement was interpreted as treason. Despite this, Sharington might have been a bit vocal about his clever trick because a bigger and dodgier Tudor courtier by the name of Thomas Seymour, 1st Baron Seymour of Sudeley caught wind. Seymour used this knowledge to drag Sharington into an even more dangerous criminal enterprise.

Coins minted early in Edward VI's reign bears the name and portrait of his dad, Henry VIII, including this example which was minted after Edward became king but before William Sharington's crimes were revealed. 1547-1549 Edward VI Hammered Silver Groat Posthumous Henry VIII Bristol Mint.

A Hairbrained Plot

Thomas Seymour and his big brother Edward Seymour, 1st Duke of Somerset, were both uncles to the orphaned Edward VI through his mother, their sister, Jane Seymour. To protect the boy-king's interests, the elder Seymour was appointed Lord Protector, effectively ruling England as regent. Thomas coveted his siblings privileged position and strove to replace him. Initially he sought the favour of his nephew but when that didn't work, he concocted plans for an armed insurrection. Insurrections need funding and that's where Sharington came in.

A dead-eyed portrait of Sharington's scheming friend, Thomas Seymour by Nicholas Denisot in the collection of the National Maritime Museum.

Seymour's plans were uncovered in dramatic fashion in January 1549. He was caught with a pistol, trying to break into the king's apartments at Hampton Court Palace in an apparent attempt to take Edward into his own custody. For this, Seymour was arrested and thrown in the Tower of London. An investigation into the plot ensued with agents sent to question all of Seymour's contacts.

Commissioners arrived in Bristol in the same month, relieving Sharington of his position and sequestering his property. Accused of treason alongside Seymour, Sharington eventually confessed to coining Testoons to 'a great sum' and falsifying records to cover his tracks.

'Yt is also objected and laied unto your charge that having knowledge that Sir William Sharington, knight, had committed treason, and otherwise wonderfully defrauded and deceiv'd the Kinges Majestie'

--- An extract from the articles of high treason brought against Thomas Seymour.

Saving His Neck

Thomas Seymour was executed for his crimes. Sharington languished in the Tower until November 1549 when he was pardoned thanks to the intervention of some powerful friends. Remarkably, he was able to buy back his estates and later went on to serve as Sheriff of Wiltshire.

An interesting and fitting punishment was wrought though. On Sharington's arrest his plate – his personal collection of gold and silver dinnerware – was confiscated and taken to the Tower. While some was returned to him, a portion was melted down in the Tower mint's crucibles to be used in coinage. That coinage was still radically debased for most of the remainder of Edward VI's reign before previous high-standards were restored under his sister, Elizabeth I.

The mint at Bristol castle continued to operate for another ten months under the supervision of Sir Thomas Chamberlain. His 'TC' mint mark can be seen on Bristol coins struck in this brief period. Perhaps due to Sharington's antics but likely because the mint of Dublin had been reestablished, the Bristol mint closed shop in late 1549, ending a riotous chapter of regional coin-related drama, tidily bookended by these two Groats.

Frequently Asked Questions

Coins were struck in Bristol from at least the 11th century from a regional mint that opened and closed depending on the coinage needs of the crown. In the Tudor period a mint operated at Bristol Castle from 1546 to 1550. Coins were again minted in Bristol during the English Civil War.

A mint operated in Bristol between 1546 and 1550. During this time coins of Henry VIII’s third coinage were struck there in gold and silver, including Testoons. Posthumous issues, minted under Edward VI in his fathers name were also struck, as was Irish coinage.

William Sharington was a Tudor nobleman who served as Under-Treasurer of the Bristol Mint in the late 1540s. He is known for an embezzlement scheme and being implicated in a plot against Edward VI as well as for owning Lacock Abbey in Wiltshire.

You might find a ‘WS’ monogram on coins minted in Bristol in the final year of Henry VIII’s reign and the first years of Edward VI’s. It was used by William Sharington, Under-Treasurer of the Bristol mint between 1546 and his arrest for embezzlement in 1549.

Gresham’s Law says that ‘bad money drives out good’. This means that if both fine and debased money is in circulation simultaneously the purer coinage will be hoarded. The concept takes its name from the Tudor financier and merchant Sir Thomas Gresham though the ‘law’ was formulated later.

The Great Debasement was an official program of debasement, instituted late in the reign of Henry VIII to increase revenue for the Crown. The practice saw the amount of gold and silver in his currency significantly reduced and continued into the reign of his son Edward VI.

Henry VIII began a programme of state-sponsored coinage debasement as a way to shore up his precarious finances. To save money on gold and silver bullion, some Tudor coins came to contain as little as one sixth of the amount of precious metal as before the Great Debasement.

Coinage with a reduced amount of precious metal was struck from 1542 though initially these debased coins were stockpiled. From 1544 they were in circulation and the percentage of gold and silver continued to decrease. This policy continued to Edward VI’s reign and into that of Elizabeth I.

All silver and gold coins, minted between 1542 and 1560 saw a reduction in fineness to varying degrees. This included Sovereigns, Half Sovereigns, Angels, Half Angels, Quarter Angels, Crowns, Half Crowns, Testoons, Groats, Half Groats, Pennies, Halfpennies and Farthings.

Initial efforts were made to counter the effects of Henry VIII’s currency debasement during the reign of Edward VI. After queen Elizabeth I came to the throne debased coinage was withdrawn from circulation and replaced with new coins of a high fineness in a move that was profitable for the crown.