1859 Ansell Sovereigns are a key acquisition for collectors of Victorian gold coins. But where did they get their name? And how can you identify an Ansell-Ribbon Sovereign?

A Reputation For Precision

Sovereigns struck at the UK's Royal Mint are renowned for beauty and their accuracy. Buyers trust that these gold coins meet strict standards for weight and purity, laid down in an Act of Parliament. Their fineness and quality is verified via an ancient public ceremony known as the Trial of the Pyx, where assayers from the Worshipful Company of Goldsmiths confirm that sample coins conform to expected specifications.

Today's testing methods are high-tech and very precise. However, in the past, a skilled and well-intentioned independent adjudicator was only as good as the facilities, equipment and methods available to them. That's why if you put a genuine George III Sovereign into a modern XRF machine, you may get a read-out that indicates a slightly different fineness than the expected 91.67% gold.

Later Sovereigns, struck from the 1850s onwards are more likely to be bang on the standard specifications. Testing has shown that the appointment of Sir John Herschel as Master of the Mint in 1850, succeeded by Professor Thomas Graham in 1855, marked a turning point in the fineness of British Sovereigns that can be attributed to each man's significant scientific background. During their tenures, part of the Mint's assaying work was farmed out to external parties and new balances and working weights were introduced. Innovative automatic weighing machines were also adopted. By the time the 1870 Coinage Act formally tightened the acceptable range for the weight and fineness of 'full' Sovereigns and Half Sovereigns, the Mint in London and the branch mint in Sydney, Australia, were already working to a narrower tolerance.

.jpg)

Chemists Sir John Herschel (left) and Thomas Graham (right) both served as Master of the Royal Mint in the mid-19th century.

Who Was George Ansell?

George Frederick Ansell (1826-1880) was born in Carshalton, Surrey, the son of a snuff manufacturer. The young Ansell was apprenticed to a surgeon and pursued medical training before turning to a career in chemistry. He studied at the Royal College of Chemistry and afterwards took a job at the newly founded Royal School of Mines as a laboratory assistant to German chemist, August Wilhelm von Hofmann. By the early 1850s he was lecturing at The Royal Panopticon of Science and Art, a short-lived but spectacular venue for recreational learning, located in Leicester Square.

Ansell's boss, Dr Hoffman, seems to have had some acquaintance with Mint Master Thomas Graham to whom he recommended the young chemist for a job at the Royal Mint. Graham's letter to the treasury proposing the appointment of Ansell to as a temporary clerk describes him as such:

'... a young man, recommended by scientific and technical information available in coining, by energy of character, and by a tried ability in the supervision of workmen - a faculty by no means common.'

Ansell started work at the Mint as a clerk for a salary of £10 a month in November 1856.

Brittle Gold From New South Wales

During Ansell's tenure at the London Mint a shipment was received from the rich gold fields of New South Wales proved unsuitable for striking Sovereigns. When annealed, the metal could be easily broken by hand. Further analysis revealed that the alloy contained lead, antimony and arsenic in improper quantities. Using this brittle gold would have risked the Mint's growing international reputation for trustworthy excellence.

Usually, such gold would have been returned to the Bank of England but in 1859 Ansell, then working in the Rolling Room, was provided with the opportunity to investigate the problem. His experiments resulted in a process whereby gold blanks were cooled suddenly by being plunged into cold water, rather than gradually as was the standard practice at the time. Applying this practice resulted in £167,539 worth of gold Sovereigns so tough that, reportedly, they could not be broken, even with a pair of pliers.

Surviving examples of these hardy 1859-dated Sovereigns are known as 'Ansell Sovereigns' or 'Brittle Sovereigns'. The Mint were so pleased with Ansell's work that they gave him a bonus of £100 (nearly £10,000 in today's money).

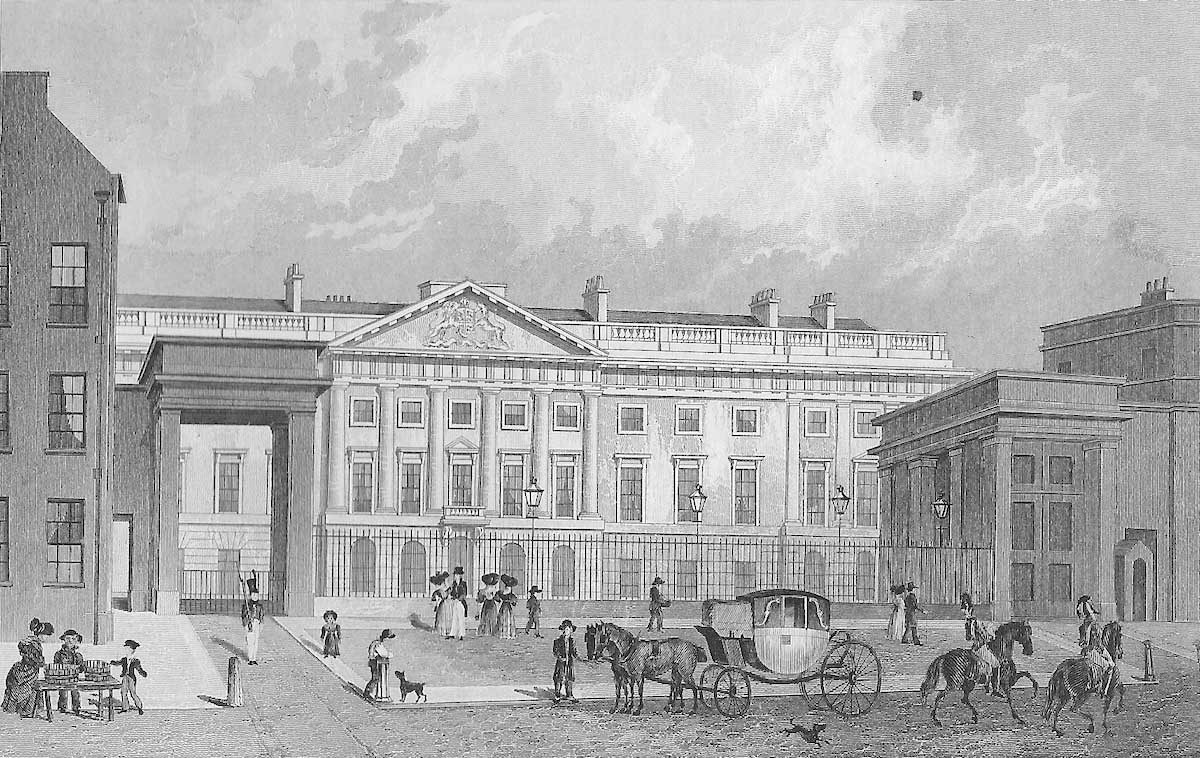

The Royal Mint's premises on Tower Hill in the early nineteenth century.

Identifying 1859 Ansell-Ribbon Sovereigns

George Ansell's 1859 Sovereigns can be distinguished from other gold coins issued in that year by a double-ribbon detail, seen just behind Queen Victoria's ear in the profile effigy by William Wyon that features on their obverse. Visible with the naked eye, this additional line on the ribbon was added intentionally by Ansell. It's why you'll sometimes hear these coins referred to as the 'Ansell-Ribbon' variation.

Otherwise, these coins are visually identical in appearance to other London Mint 'Shield Back' Sovereigns with the same date. The year appears below the royal portrait with the legend 'VICTORIA DEI GRATIA' ('Victoria by the grace of God') around. The reverse shows Jean Baptiste Merlen's crowned, quartered shield of arms design with oak and laurel leaves and the words 'BRITANNIARUM REGINA FID: DEF:' ('Victoria by the Grace of God, Queen of the Britains, Defender of the Faith').

Obverse and reverse of a scarce 1859 Ansell Sovereign.

Are Ansell Sovereigns Rare?

Ansell's 1859 Sovereigns did circulate, the ribbon detail likely acting as an identifier to see how they would wear.

While thousands of Ansell Sovereigns were struck very few survive today: reportedly just 11-20 examples.

Marsh rates Ansell Sovereigns R4, indicating that they're among the rarest known gold Sovereigns. They remain sought after by collectors with high-grade coins selling for five figures at auction.

.jpg)

It's the extra line on the hair ribbon behind Queen Victoria's ear that identifies an 1859 Ansell Sovereign.

The Royal Mint: Its Working, Conduct, and Operations

While Ansell's work on the 1859 Sovereign was praised by his superiors, his strong opinions about how the Mint should be run would eventually cost him his job.

After his dismissal, Ansell retained an interest in coin production, writing a treatise on the subject that he would later extend into a longer published work, titled The Royal Mint: Its Working, Conduct, and Operations, Fully and Practically Explained. It's a very useful volume, packed with technical detail as well as lots of direct criticisms of individual members of the Mint's staff and broader statements on mismanagement and wasteful practices. It’s said that his criticisms influenced the 1870 Coinage Act but other contemporary commentators and modern numismatists are a bit sceptical of some of Ansell's observations.

Later in life, Ansell practised as an analytical chemist, investigating the danger of explosions in collieries. In 1865 he patented a firedamp indicator, capable of detecting flammable gas underground, which was successfully adopted in mines across Britain. He died at home in Islington in 1880 at the age of 54.

Frequently Asked Questions

Ansell Sovereigns or Ansell-Ribbon Sovereigns are a batch of British gold Sovereigns struck in 1859 from specially treated gold. They are identified by a ribbon detail on the obverse.

Supposedly, some 167,539 Sovereigns were struck by the Royal Mint with the so-called 'Ansell-Ribbon' variation. Very few of these have survived, perhaps less than 20.

Most sources agree that just 167,539 Ansell Sovereigns were struck at the Royal Mint in 1859. Of this few are understood to have survived: perhaps as little as 20.

1859 Ansell Sovereigns are made from a specially treated batch of 22-carat gold. They get their name from the chemist who created them: George Ansell.

Genuine 1859 Ansell Sovereigns are made of 22-carat gold and weigh 7.98 grams. These rare coins are reputedly very tough and hard to break but we wouldn't recommend damaging one!

Ansell-Ribbon Sovereigns can be identified by an extra line that appears on the ribbon behind Queen Victoria’s ear on the obverse portrait. Standard 1859 Sovereigns have a plain ribbon.

George Ansell was an English chemist and assayer who worked for the Royal Mint in the 1850s and 1860s. He lends his name to the rare 1859 Ansell Sovereign and wrote widely on minting.

.jpg)